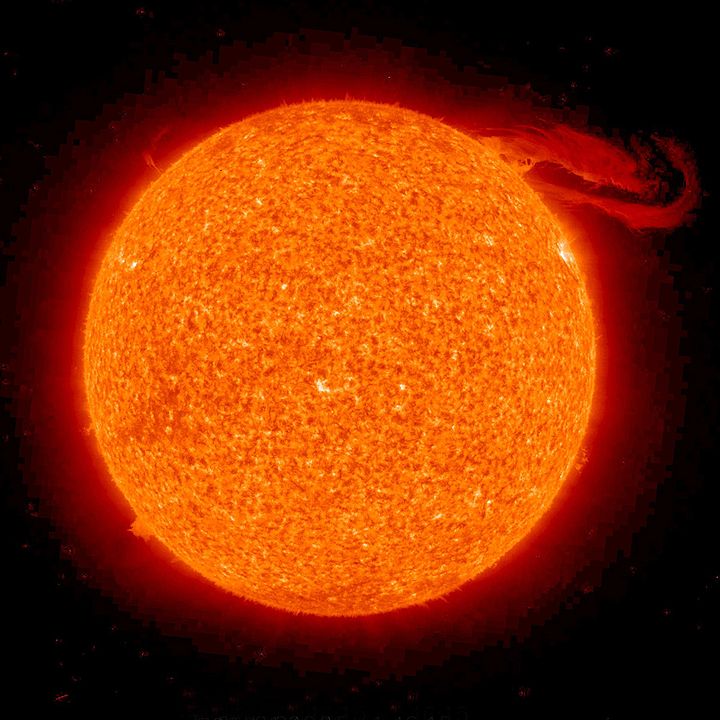

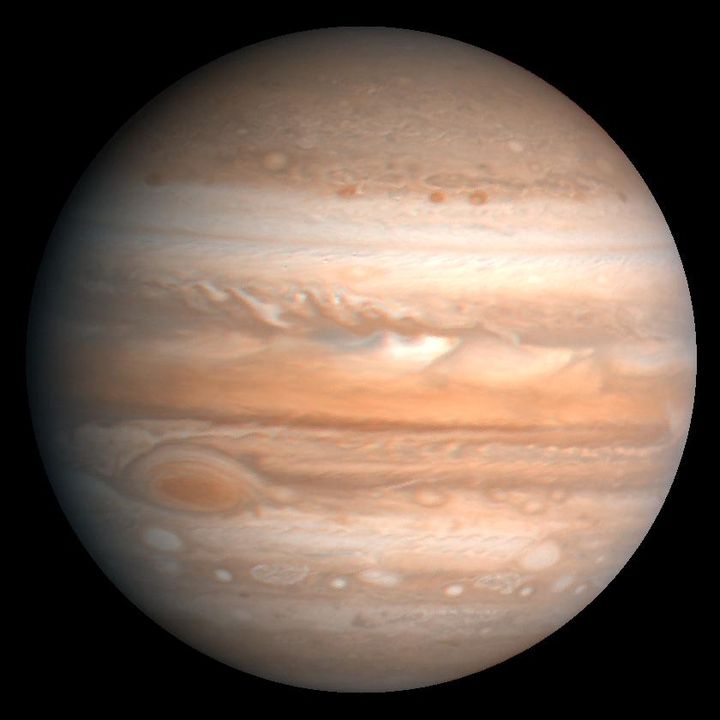

Why isn’t stuff like the sun and Jupiter blurry around the edges? They seem to look like their edges are sharp and distinct:

This was surprising to me when I started thinking about it a few months ago. I thought they were made out of gas, and my understanding was that when you have a bunch of gas gravitationally attracted to something, it ends up spreading out. For example, the Earth’s atmosphere decays in pressure gradually from the surface up to space. I would have thought that Jupiter would also decay in pressure gradually, which I’d have thought would make it look blurry around the edges. What gives?

A couple months ago, I asked this to Sebastian Conybeare and we tried to calculate the answer to a simple version of this question, only to be mystified by our calculations giving us answers that seemed physically impossible. Sebastian eventually figured out what was going on, and I think that it taught me something really interesting about statistical mechanics.

Sebastian and I tried to answer the following question: Suppose you have a bunch of ideal gas out in space, attracted to itself by gravity. You leave it for a long time and come back to observe it. What’s the density distribution of the gas?

Our guess is that it would end up being spherically symmetric, with higher density in the middle and density that falls off to the sides.

So we tried to calculate the answer. Here’s the calculation we tried to do. Imagine that there are a bunch of weightless thin sheets suspended in the atmosphere, buffeted by the pressure above and below. If the atmosphere is at equilibrium, the sheets won’t move, because the pressure distribution isn’t changing. Now, we can consider each of these sections of atmosphere. Each of these experiences a compressive force from all the rest of the atmosphere above it resting on it, and also experiences an expansive force from its own pressure. If things are at equilibrium, these forces are equal. So to calculate the equilibrium, we just make an equation saying that these two forces are equal and solve the resulting equation for the density as a function of height.

But the answers you get don’t make sense. In particular, the equation you get for density implies that the atmosphere extends infinitely, and pressure doesn’t go to zero.

We were pretty surprised by this answer, and pretty skeptical of our algebra, so we tried answering a similar simpler question. The Earth’s atmosphere has a density which decays approximately exponentially with height. To derive this, you approximate gravity as constant. What happens if you instead relax this assumption and treat gravity as the inverse square law force that it actually is? We did similar math on that problem and got another answer that doesn’t normalize.

At this point, Sebastian realized what was going on. The problem is escape velocities. When you have a bunch of particles orbiting around a planet, exchanging energy via gravitational interactions, it’s possible for one of the particles to randomly obtain enough energy that it can escape the gravitational pull of the planet and shoot off towards infinity. This happens over and over again until the remaining gravitationally bound particles don’t have enough energy for any of them to escape. This happens in both the self-gravity case and the atmosphere-around-a-planet case.

Sebastian looked into this a bit more and then found that if you have an ideal gas at thermal equilibrium in some potential, the density at a position is proportional to exp(-V), where V is proportional to the potential energy at that position. In both the cases we discussed here, the potential goes to zero, which means that according to that rule the density in thermal equilibrium never gets below some threshold, no matter how far away from the center of mass you get. So you definitely don’t get a normalizable density function.

So atmospheres and gravitationally bound clumps of mass are both ephemeral; after you wait long enough, they’ve all dissipated. (And for bonus fun: The fact that they don’t have thermal equilibrium is basically a result of the fact that you’re always going to be able to look at the density distribution and figure out how long the system has been evolving, because the longer you wait the further out the particles will have spread.)

I guess one moral of this story is that thermal equilibrium doesn’t really happen in the real world, at least according to classical mechanics. Gravitational and electromagnetic forces go to zero at infinity, which means that no system held together by gravity or electric forces is stable. I feel like it would have been good if this fact had been mentioned when I was learning statistical mechanics.

I’m amused by how when I saw the calculations demonstrating that atmospheres are in thermal equilibrium with exponentially decaying pressure, it wasn’t explained to me that approximating gravity as constant isn’t just algebraically convenient, it’s required to get a solution at all.

After I posted this to Facebook, a bunch of people replied with things like

As far as the sun is concerned, the sharp edge you’re seeing is not a density dropoff, but is instead the depth at which photons can escape. There’s lots of gas that extends past that point but which is invisible.

I think that this misses my core point. Here’s a graph of the density of the Sun as a function of radius (from here):

And another, which particularly emphasises the rapid dropoff at the edge:

And here’s Jupiter, from here:

Both of these are extremely rapid drops at the edge; I remain confused.

I’m sure that the answer is obvious to someone, but I still don’t know what it is, and don’t feel bothered enough to spend more time looking it up.